At the Royal Horticultural Society (RHS), Wisley, in the heart of the UK Surrey countryside, Gemma Hardy and Jassy Drakulic led a workshop to address ‘fungal blindness’.

April 11, 2024

FFungi Staff

FFungi Volunteer

Sustainability consultant

This article was written by Gemma Hardy and reflects her personal experience and opinions.

“They are everywhere and yet nowhere.” (Sheldrake, 2022).

This quote from UK mycologist Merlin Sheldrake describes how despite being the most ubiquitous organism on earth, many of us struggle to recognise fungi’s existence. This phenomenon is called fungal blindness; the failure to appreciate the fundamental importance of fungi. Much like plants, fungi often dwell in the shadows of our awareness, with our biological inclination drawing us towards larger, more charismatic creatures of the animal kingdom. Just as plant blindness obscures the significance of plants, fungal blindness obscures the essential contribution of fungi to the intricate web of life.

It was an exceptionally hot June day, when 43 teenage boys tumbled out of their school coaches, arriving at RHS, Wisley for two workshops – one on ‘Plant Pathology’, part of the National Curriculum for Biology and the other on ‘The Art of Noticing Fungi’, co-designed by an MSc Sustainability student, Gemma Hardy, and resident mycologist, Jassy Drakulic.

The workshop began with Jassy giving a brief overview of what a mycologist might do on a typical ‘foray’, including the notes they might take and the tools they might use. Armed with field notebooks and pencils, the students filed outside into the ‘Wildlife Garden’ to observe any signs of fungi. Given the less-than-favourable weather conditions (for fungi), macrofungi spots were sparse. Large, perennial Ganoderma sp. brackets were found around the base of a mature hornbeam and some shrivelled turkey tail fans adorned some silver birch cut logs. Mycelium found just below the bark of a large rotting oak offered a fresher find. Students were encouraged to look at the fungi’s surroundings, substrate, aesthetic form including size, shape, and colour, as well as texture and smell. Making field observations places fungi within the complexity of larger systems and helps them be perceived as more authentic and relevant by the observer. Even this ‘tough crowd’ for engagement eagerly asked questions, clearly taking interest in these strange forms, and remarking how they “…hadn’t really learnt much about them in biology”.

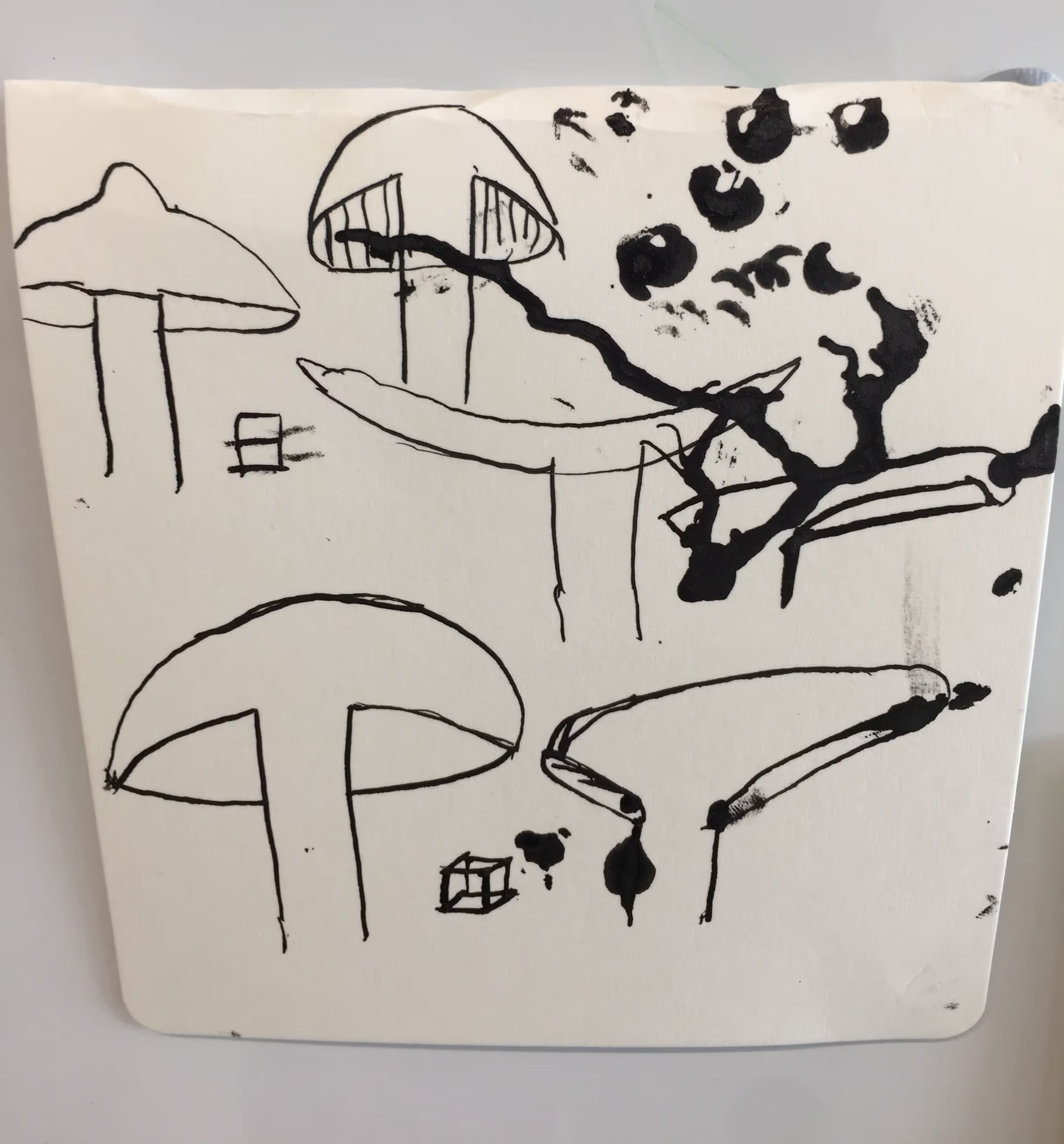

Returning inside, students had the opportunity to observe fungi at the micro- scale, with pre-made spore slides of Earthball and Puffball spores. However, this workshop was designed to encourage active participation, including creative elements, which commonly reinforces learning and can increase empathy for a subject. The room was filled with mycology books containing photographs, keys, morphological diagrams, and artistic impressions of fungi. Dried and fresh specimens were also available for the students to touch, handle and smell. The students were encouraged to draw, using the medium of a nib and ‘spore ink’ from the Shaggy Inkcap, whatever intricacies from the resources or their field notes had caught their attention. ‘Noticing’, in this case at both the macro and micro scale, is a practice relevant to theories of attention, interest, nature connection and ethics of care (Edwards et.al, 2021).

What ensued was quite surprising, even for the student’s head teacher. The room was filled with excited chatter as the students readily engaged, especially in the drawing element. Whilst cradling a vivid orange cordyceps, one student eagerly made the association with dramatic stories he had heard of this ‘zombie’ fungus. Another student re-enacted to his peers the sound of the ‘PUFF’ made by the explosion of a giant puffball from his granny’s garden. Creativity is often used within early learning but more rarely used with older students; a missed opportunity when there is so much evidence linked to effective environmental learning.

Whilst there was a clear curiosity with fungi, the research revealed a comparatively basic understanding of this third kingdom of life. Given that the UK National Curriculum (Key Stage 4) mentions fungi just twice, compared to 69 and 72 mentions for animals and plants (2023), this ignorance is unsurprising. However, the lack of progress in fungal education only amplifies the importance of cross-curricular outreach such as this workshop. Furthermore, to see learning had occurred in such a short timeframe reinforces outreach can play a significant role in addressing ‘fungal blindness’.

This was one of two case studies explored to see the effects of a creative intervention on fungal blindness. Written by Gemma Hardy, author of the thesis titled: 'Fungi & Me: An exploratory study into how we perceive fungi and the implications for outreach, intending to challenge Fungal Blindness'. A journal article with full results will be published in due course.